For years, lawmakers and academics have been racking their brains for a solution to the problem of Lebanese Pound deposits in commercial banks. Countless proposals have emerged—many of them logical, fair, and seemingly feasible. Yet none of these ideas has ever found its way to implementation, however sound they appear. Why? Simply because they fail to start from the right question, which great thinkers have always considered the true entry point to solving any problem. The question is: Do Lebanon’s officials, across political and financial authorities, even have any interest in ending the collapse?

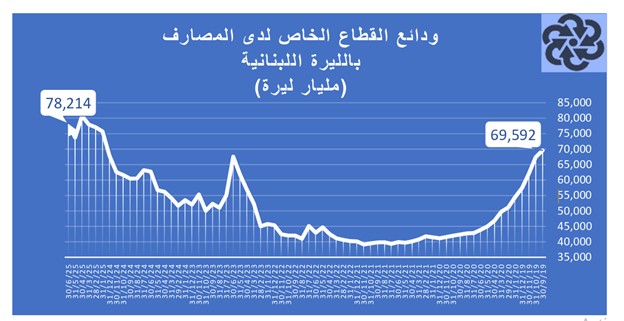

On the eve of the economic meltdown, deposits in Lebanese pounds stood at 69.6 trillion Pound—worth $46.4 billion at the time. As the attached chart shows, those deposits shrank dramatically during the first three years of the crisis as depositors rushed to protect their savings against the Pound’s decline. Yet starting in February 2023, the trend reversed, coinciding with the Central Bank’s decision to raise the official exchange rate from 1,500 to 15,000 Pound per dollar, even as the parallel market rate spiraled toward 140,000.

By mid-2025, deposits in the Pound reached 78.2 trillion. But at a market rate of 89,500 Pound to the dollar, that sum amounted to just $873 million in real value. In other words, depositors have lost roughly 98 percent of their savings.

(Source: Monthly Economic Bulletin of the Association of Banks in Lebanon)

(Source: Monthly Economic Bulletin of the Association of Banks in Lebanon)

(Source: Monthly Economic Bulletin of the Association of Banks in Lebanon)

Why Pound Deposits Rose

Paradoxically, Pound deposits have risen by 8.6 trillion rather than shrinking, unlike dollar deposits. According to financial consultant Dr. Ghassan Chammas, several factors explain this:

- The inflow of “fresh” Pound deposits, lured by high interest rates, with larger nominal amounts due to the collapse in the exchange rate.

- Private sector employers continue to deposit significant amounts in Pound to cover salaries, which ballooned after the minimum wage jumped from 675,000 to 28 million Pound.

- The “Sayrafa” phase, when depositors carried bags of Pounds to banks to convert them into dollars.

- The simple fact that depositors stopped withdrawing the Pound once it had lost 98 percent of its purchasing power.

In general, says Chammas, the swelling size of Pound deposits reflects the Central Bank’s money-printing spree. But the real question is how to solve this problem fairly for three key categories of depositors:

- Retirees who placed end-of-service indemnities—whether from public or private sector jobs—into Pound accounts.

- Unions, independent institutions, and funds, most notably the National Social Security Fund.

- Depositors are enticed by banks to convert their dollar savings into pounds with promises of high interest.

The Boustani Proposal

Whether in “fresh Pound” or so-called “bank Pound” (trapped in the system), the reality is the same: these deposits have lost nearly all value. In an attempt to restore a measure of fairness, MP Farid Boustani introduced a draft law addressing Pound deposits belonging to individuals and companies, placed in Lebanese banks before October 17, 2019, and still there on the law’s issuance date.

The plan would calculate these deposits at 20 percent of the prevailing market exchange rate. For example, a deposit of 15 million Pound would be treated as $10,000, multiplied by 17,900 Pound (20 percent of a hypothetical market rate), yielding 179 million Pound. Crucially, this sum could only be used to pay taxes and fees. Annual use would be capped at the equivalent of $100,000 per taxpayer, based on the market rate at the time of payment.

It is a significant step—an attempt to address one of the deepest social and economic consequences of the crisis, while balancing depositor rights with fiscal needs. The gap between nominal and adjusted values would be covered by the Treasury as a form of state-backed support for Pound depositors.

A Proposal Doomed by Reality

Yet even assuming taxes could be paid using deposits multiplied 17-fold, the state would end up with massive volumes of Pounds it cannot realistically spend. If funneled into salaries, wages, or other expenses, the surplus liquidity would flood the market, fueling demand for dollars and triggering another collapse in the exchange rate.

This, analysts argue, explains why the government has left untouched nearly $8 billion accumulated in its Central Bank account—funds mostly denominated in Pound—despite enormous spending needs. The Finance Ministry and the Central Bank are unlikely to endorse such a risky plan.

From another angle, any Central Bank solution that tries to compensate depositors would, by definition, involve printing or injecting vast amounts of Pounds. That, warns Chammas, would inevitably drive the exchange rate beyond its current 89,500 per dollar, sabotaging efforts to curb inflation. In turn, the newly multiplied Pound deposits would quickly lose even more of their real value, fueling demands for higher public sector wages and higher private sector minimum salaries. The cycle of devaluation and inflation would resume unchecked.

The grim truth, however painful, is that Pound deposits have lost their value and become the ultimate “victim” of the crisis—in the fullest sense of the word: an injured party subjected to harm so severe that full compensation may be impossible.

Please post your comments on:

comment@alsafanews.com

Politics

Politics